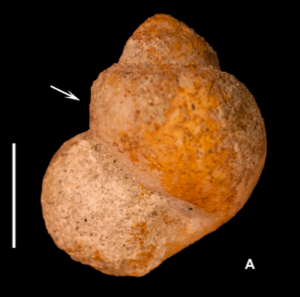

Ranjeev passed the final defense of the MS thesis this morning after a lively presentation and discussion of Paleoecology of the Freshwater Ampullariidae from the Late Oligocene Nsungwe Formation of Tanzania. Ranjeev’s thesis describes a new fauna of freshwater gastropods documenting speciation during the initiation of the East African Rift Valley. It’s a great study of an interesting and significant set of fossils. Congratulations, Ranjeev!

Ranjeev passed the final defense of the MS thesis this morning after a lively presentation and discussion of Paleoecology of the Freshwater Ampullariidae from the Late Oligocene Nsungwe Formation of Tanzania. Ranjeev’s thesis describes a new fauna of freshwater gastropods documenting speciation during the initiation of the East African Rift Valley. It’s a great study of an interesting and significant set of fossils. Congratulations, Ranjeev!

Nilmani passes her final defense!

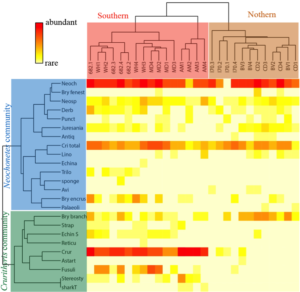

Nilmani is now a Master of Science! She successfully defended her thesis titled: Hierarchical Spatial Patterns in Paleocommunities of the Late Pennsylvanian Ames Limestone. Nilmani did a really nice job in her thesis analyzing and interpreting regional vs. local differentiation in contemporanous shallow marine communities across southeastern Ohio. Congratulations, Nilmani!

Nilmani is now a Master of Science! She successfully defended her thesis titled: Hierarchical Spatial Patterns in Paleocommunities of the Late Pennsylvanian Ames Limestone. Nilmani did a really nice job in her thesis analyzing and interpreting regional vs. local differentiation in contemporanous shallow marine communities across southeastern Ohio. Congratulations, Nilmani!

Reflections on the International Biogeography Society Meeting in Tucson: Celebrating diversity and deep time

This post was initially written as a guest blog for the International Biogeography Society blog

The International Biogeography Society Biennial Conference is one of my favorite meetings to attend. These conferences consistently profile outstanding and cutting edge science, opportunities to interact with a set of colleagues that I don’t have the opportunity to see at my paleontology-centric conferences, and interesting destinations to explore. This year’s conference in Tucson hit the mark in all areas.

A key strength of IBS conferences is that they are fundamentally a celebration of diversity in many ways: diversity of approaches ranging from molecular to big data and ecological to phylogenetic frameworks; diversity of focal ecosystems and taxa; diversity of temporal lens from modern to deep time; diversity of nationalities and cultures; diversity of genders and identities. This diversity makes the scientific contributions and opportunities so much stronger. Developing such a diverse conference is not a coincidence, the IBS board and meeting organizers actively work to promote scientific and culture diversity. And the dedication and hard work pays off. For example, someone like me, who studies paleobiogeography of marine life from 400 million years ago feels at home with colleagues studying geographic structure of genetic variation in modern tree species.

From my perspective, two aspects of this year’s IBS conference particularly struck me: the increasing inclusion of a deep time perspective and fossil data and increasing recognition and participation of women in biogeography.

Each of the symposia featured at least one talk involving paleodata. The “Modeling large-scale ecological and evolutionary dynamics” symposium featured paleo data in nearly every talk and showcased a wide range of paleo data from historical records to the Pleistocene. Contributed sessions, posters, and mini-talks also prominently focused on the relevance of paleodata, including analyses that employed Paleozoic data to address questions relevant to modern biodiversity concerns (abstract book here).

Geologic and paleontological data, particularly the breakup of Pangaea and the waxing and waning of the Pleistocene ice sheets, have long been incorporated in biogeographic analyses. What was exciting about this meeting is the fact that paleodata beyond those two cases are being employed and being employed broadly within the field in many different contexts ranging from species distribution models, quantifying community functioning and species richness processes, and calibrating projections of biotic impacts of future climate changes.

Rising above this pervasive paleontological mist was the fact that the winners of the MacArthur & Wilson and the Alfred Russell Wallace Awards, Jessica Blois and Margaret Davis, are paleobiogeographers, which further underscores the significance that the field ascribes to research emphasizing fossil data.

Both awardees are also women, which leads to my second point. This meeting celebrated the accomplishments of outstanding women in biogeography, like Jessica and Margaret, and at the same time acknowledged and celebrated the additional hurdles and barriers that were (and still are) faced by women in science. Steve Jackson, in his citation of Margaret Davis, provided a wonderful discussion that contextualized some of the hurdles that Margaret faced as the sole women in pollen analysis, the significance of her indomitable spirit, and the inspiration she has provided to others.

Today, women are not usually alone in our departments or subdisciplines, but we and members of other underrepresented groups still face obstacles, additional requests on our time as token representatives, and implicit bias in reviews and in other contexts. But meetings like IBS, where a group of women met at 7:30 am over coffee to discuss shared issues and plan a support group and where we have lunch mentoring groups that discuss early career issues, provide clear and positive steps forward.

Women have been leaders in biogeography for many years, as evidenced by the Margaret Davis’s well deserved Wallace award, and women are poised to continue leading and innovating, as evidenced by female students winning 3 of 5 poster awards.

I ended the conference by raising my glass with a group of a dozen female paleobiogeographers. For me it was a fitting end to a conference that celebrated diversity of science, of timescales, and of individuals.

Winter Outreach: Important and rewarding work

Although it’s a bit cold during a (typical) Ohio winter to do a lot of field-based outreach, I try to keep busy with indoor outreach opportunities. This winter, I’ve been working with kindergarteners, grades 4-9 science teachers, and a nearby public library to communicate the importance of understanding Earth’s history. I usually forget to take photos (which makes a less interesting blog), but I thought two events this winter were worth mentioning on the lab blog anyway.

#1: Continuing our year-long SIPLAS program (see earlier post), I was able to lead a lesson plan on understanding climate change data, decoding fake scientific news stories, and accessing government climate data with our grades 4-9 teacher group. My colleague, Danielle Dani (the science education faculty member), did a great job leading off with a provocative question about whether the EPA should establish CO2 emissions targets which allowed the participants to immediately grasp the real-life link between themselves and climate science. Then we plotted sea ice and snow cover extent data from NOAA and used that to exams and debunk a fake news article.* It felt really great to be able to help this really super group of teachers develop stronger skills to cope with teaching a facts-based, strong science curriculum. Such tools are increasingly important given the dramatic anti-science rhetoric coming from the current administration, and it is imperative that professional scientists of all types develop closer ties to the public and increase our outreach during this difficult times for our nation. It is critical to the next generation understands the promise and importance of a scientific understanding for climate, medicine, and pollution to protect and preserve our quality of living and environment in both the short and long term.

*Thanks for Brad Deline for sharing an earlier version of this exercise. An example of scientists collaborating for the greater good!

#2: I gave a public program about my Antarctic research for The Plains Library (The Plains is next town north of Athens). Sure, I conducted that field work in November-December 2004, but stories of adventure and intense field conditions paired with really cool scientific results never really gets old. Seriously though, the combination of discovery, adventure, and hypothesis-grounded science really is a slam dunk for outreach. Most geologists have some great fields stories that can be worked into outreach is a really positive and effective way. In the case of my group, they were enthralled by the natural history of penguins (which had nothing to do with my primary research, but is a great way to discuss how climate change impacts species people care about), how to survive in subzero conditions (a really fantastic young woman even modeled my Antarctic gear as part of my explanation of our clothing), and the realities of camping on the ice (such as returning all recyclables and solid waste –even human–back to the US for disposal). I was also able to roll in plate tectonics, fossil preservation, and even a sidebar about local rocks of The Plains. Overall, it was a fun event, mostly because the audience was so interested and asked such great questions. Most of the pre-adult group were girls, who had awesome questions. Their parents had to drag them out of the library at the end of the evening. And that is awesome–girls so excited about science that they don’t want to stop talking about science.

It is imperative that professional scientists spend time sparking interest about what we do in young people. And it is critical that we have ALL types of scientists: women and men of all races, cultures, and identities interacting with the public. It is hard to imagine that you can be a scientist without ever seeing anyone like you in science. So we need ALL of us showing ALL of our society that together we can be stronger, we can improve our understanding of the world in which we live and we can innovate for a better tomorrow.